The complete truth, before reconciliation.

Forwarding this email, or posting it on social media along with some words about why you support us helps to expand our reach!

What do Princess Diana, Mother Teresa, and Canadian Indian Residential Schools have in common? They all died in 1997. No, that’s not a typo; the last Residential School (Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut) shut down the same year Titanic hit theatres. That means the government continued to commit genocide in front of our eyes for more than a decade after we had access to cellphones and the internet.

1997 wasn’t that long ago—a mere 28 years—but the language colonial institutions employ to refer to Residential Schools does a great job of making you think otherwise. For the fifth annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (colloquially known as Orange Shirt Day), we will once again be invited to reflect on the history of Residential Schools and the harm they had on survivors and their kin. My emphasis is meant to underscore the tense in which the state would prefer you engage with the idea of Residential Schools: the past. Why is that? Because the further away it feels from the present, the less this current chapter of white supremacy has to atone for. Controlling the language of reconciliation allows the state to set the terms for reconciliation—which ultimately means avoiding any real accountability. Make no mistake; it’s an intentional tactic that relegates Canada’s genocide of Indigenous Peoples to a fever dream rather than the ongoing reality that it is.

In his forward to Glen Coulthard’s Red Skin White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, Taiaiake Alfred writes:

[I]n Canada today "settlement" of conflict means putting the past behind us, a willful forgetting of the crimes that have stained the psyche of this country for so long, a conspiracy of collective ignorance, turning a blind eye to the ongoing crimes of theft, fraud, and abuse against the original people of the land that are still the unacceptable everyday reality in Canada. So how could we settle and accept and not question and challenge the naturalized injustice that frames and shapes and gives character to our lives?

Even when they (any institutions or individuals that uphold the colonialism and racial capitalism that led to Residential Schools) speak in the present tense, it’s often just about engaging with this legacy (another word that couches colonial harm in the past) and educating oneself about it. While this is indeed a good place to start, it’s important to understand that real reconciliation means decolonization—but like we said in our July newsletter, that would put the government out of business. As Coulthard himself writes in Red Skin White Masks: “[C]olonial powers will only recognize the collective rights and identities of Indigenous peoples insofar as this recognition does not throw into question the background legal, political, and economic framework of the colonial relationship itself.” That background, of course, being one of racism, violence, and illegitimacy.

So what are we left with? One day a year to commemorate the 4,037 documented Residential School deaths (the true number is estimated to be between 6,000 and 25,000). Makes ya think: would the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation even exist if not for the pressure placed on the government after the discovery of mass graves on Residential School grounds? In this context, regardless of it being one of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action (of which only 15 have been completed), it’s hard to see it as anything other than damage control (and it’s hard to ignore the fact that it was one of the easier Calls to enact—all they had to do was piggyback on the existing Indigenous-led Orange Shirt Day movement).

A day of reflection costs the state nothing: no structural change, no transfer of power or resources, no disruption of the colonial systems that continue to murder the original people of the land. It merely soothes the settler conscience and allows the machinery of oppression to keep chugging along while giving governments, institutions, and corporations the chance to brand themselves as allies without ever ceding control (to say nothing of the myriad ways in which Orange Shirt Day has been co-opted and bastardized—a couple of years ago, Nii’Kinaaganaa’s founder drove by an elementary school class during recess that was “commemorating” Orange Shirt Day by having a dance party).

Now, you might ask “what about the settlements paid out to survivors?” to which I would say “what about them?” Allow me to do some crude math. Canada awarded $3 billion to 28,000 survivors and began the compensation process in 2007. For the sake of argument, let’s say that money was split evenly among survivors (it wasn’t—some only received the $10,000 base compensation). That would give each person $107,142. And a quick search estimates that a single person’s monthly living costs in 2007 were about $1,716. That would mean each survivor would receive just over five years worth of living costs. Does that seem like fair compensation for a lifetime of harm? Not to mention the time costs and re-traumatization the compensation process most likely effected. Even if every survivor was monetarily set for life, the mechanisms of colonialism would still be in place, the generational trauma still destroying everything in its path. It’s akin to someone chopping your hands off, you walking into the ER, the doctor wiping the blood away, and pulling down their mask to reveal they were the one who maimed you: “all better!”

When it comes down to it, the colonial government’s hollow and sanitized version of reconciliation requires nothing more than accepting Canada’s sordid past. But reconciliation without restitution, land back, and power is both an illusion and a delusion—and a dangerous one at that. Acceptance without action is the path towards normalization, and normalization is the path towards recurrence. At the risk of sounding obvious, true decolonization doesn’t accept colonialism—it rejects it. And since the government won’t hand back the reins, it’s up to the people to organize and take them back by any means necessary. This is why fascism is on the rise: colonial governments know they won’t be in the driver’s seat for much longer so they strengthen their grip on the wheel and clutch what remaining power they do have.

But they’re running out of gas.

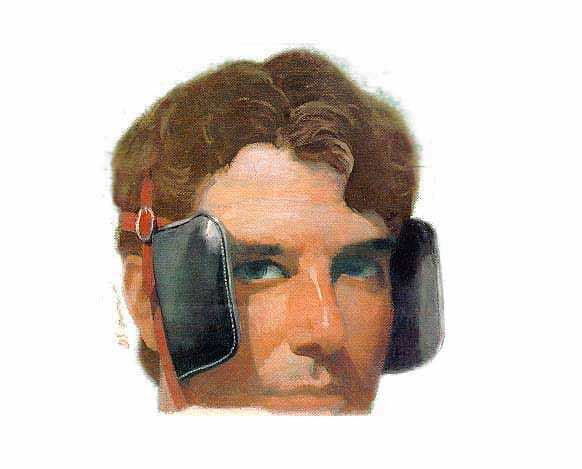

As the global population finally begins to demonstrate mass Palestinian solidarity in opposition to another genocide of Indigenous Peoples being committed in front of our eyes, it’s no coincidence that Canada (whose recognition of Palestinian statehood—purely a symbolic gesture at this point—is contingent on meeting certain ludicrous conditions, like demilitarization, which would pave the way for Israel to complete its genocidal campaign) is desperately lunging for more “nation-building” fossil fuel projects that will continue to infringe upon Indigenous rights and exacerbate the climate crisis. What’s behind this push for more capital and power? The colonists know the tide is changing. They know they’re beginning to lose public favour. And they know we know that true decolonization is the only way to avoid planetary extinction. This is their swan song and as long as there’s money in the ground, they will continue to sing—which is why WE must continue to organize. Oh and if you think this is exclusively about mitigating the effects of US tariffs and the trade war, this is what you look like:

Now tell me what you think THESE things have in common:

-Seniors for Climate Action Now

-Educators for Palestine

-The Communist Workers Circle

-The Canadian Union of Postal Workers

-Spring magazine

-Justice for Workers

-Indigenous speakers

-People with trans rights pins

-Musicians, volunteers, people of all ages, races, and ethnicities

-A free ice cream truck

If you guessed that they all organized to show up and reject white nationalism in Canada, you are correct!

On September 13th, I attended the “No to Hate” counter-protest of an anti-immigrant contingent of “Canada First” racists in Christie Pits park and I’m happy to report that our group (numbering in the thousands) significantly outnumbered the racists (just a couple dozen). They showed up with hate in their hearts and Charlie Kirk on their posters (same thing), but we showed up with love and the strength of several diverse affinity groups united by a single goal: to say no to hate by driving these racists driven by propaganda and paranoia out of the park.

This is the kind of coalition-building that will become increasingly necessary as the West begins to bare more teeth in response to its own death rattle. A coalition forms when people or groups with different identities and capabilities join forces to prioritize a shared agenda—aka, to get shit done. Its diversity is what allows it to leverage different skills, resources, and communities to better accomplish its goal or drive a movement ahead. Speaking on coalitions and the growing Jewish presence in the Palestinian solidarity movement, Rabbi Brant Rosen said “Every group is important and every group has a role to play.”

Coalitions give us a better chance of shifting power by applying the political, social, and economic pressure necessary to make real change. Instead of a single person showing up somewhere in an orange shirt for one day, we suddenly have the ability to show up en masse, every day: at blockades, court hearings, school boards, workplaces, legislatures, etc. You can block out one person wearing orange, but you can’t block out the sun.

A great example of coalition-building is the relationship Nii’kinaaganaa has forged with Resource Movement: a community that organizes and mobilizes young people with class and wealth privilege to redistribute their abundance in pursuit of a more just and equitable world. Since partnering together, Resource Movement has been able to consistently top up our mutual aid funds, which means we can say yes to more requests—and that means less Indigenous people going hungry, not being able to secure housing, or falling out of touch with their cultural practices and ways of life. Most importantly, these funds and resources are offered to us with no strings attached because we share a similar goal: righting the wrongs of colonialism and white privilege.

To quote Rosen again, coalitions are about “showing the world what the world should look like in real time.” And that’s exactly what Resource Movement does: they provide us with a model of how people can make a difference using the privilege that has been afforded to them by inequity. Just the fact that Resource Movement exists at all disproves the anti-socialist myth that humans are greedy by nature and signals yet another turning of the tides as more people are exposed to the atrocities of colonialism and learn that the only way forward is decolonialism.

And with that, let’s meet one of the organizers we support who works to help Indigenous people meet their survival needs as they fight against the injustices of colonialism.

Terrill Tailfeathers is a member of the Blackfoot Confederacy and an organizer currently working in Mohkínstsis/Calgary. Born in a segregated hospital and raised on the Blood Indian Reserve, also known as Kainai Nation, Terrill uses his large social media following to bring awareness to different organizations (like the abolitionist collective, Walls Down) and crowdfunding initiatives for at-risk youth (often within the 2SLGBTQIA+ community) and other marginalized individuals struggling to survive. This could mean helping people pay for their phones and rent, providing food and hygiene essentials to those in need, connecting people in crisis to support services, and just being someone they can reach out and talk to.

One of the things that makes Terrill uniquely qualified to support the dispossessed is his ability to relate to them: "That feeling where you want to give up your whole world because you've got nothing—I've been there." Reflecting on a time when he was able to provide material support (with the help of your donations) and hope to a family in need during the holidays, Terrill said:

They were really stressed out because the father had lost his job and one of the kids was sick in the hospital. I was able to raise enough funds to "save their Christmas"—in their words. And when the kids sent me a message saying "Thanks for all the help; Christmas has been really hard on our dad" and when the dad called to say thanks and he was bawling—it just makes you feel really good to be able to help.

But Terrill isn't doing this to feel good. These are acts of life-preserving resistance against the very reason this kind of help is needed in the first place—AKA: mutual aid. The vulnerable populations Terrill works with are vulnerable "because of ongoing colonialism" and “because they don’t have the supports and safety nets that are actually needed." To put it another way: the true problem is who caused the problem.

Having spent time with the Tiny House Warriors (helping to amplify their struggle, raise money, maintain camp, and bear witness to Canada’s ongoing Indigenous land theft and violence against land defenders), Terrill understands that no matter how many statutory hollowdays the state creates to try and cover their ass, the deleterious effects of colonialism and white supremacy will continue to upend the lives of the original peoples of the land. When it comes to real reconciliation, engagement with and education about the past are certainly important—but the only way we’re going to achieve decolonization is through action right now. If we don’t act now, the future will be one where the same stories continue to be told: stories of children lost, communities dispossessed, and governments performing reconciliation while perpetuating harm. Either we build community and coalitions strong enough to force change, or we accept that “Truth and Reconciliation” will remain another hollow component of Canada’s nation-building project. Real reconciliation is the dismantling of colonial power—and that can only be won together.

Thanks for reading and supporting,

The Nii’kinaaganaa Team

“Put love in front of you when you get up in the morning and it will guide you to a beautiful place.”

-Ma-Nee Chacaby, LGBTQ&A